I was recently made aware of AnyDVD HD, a piece of software that acts as a real-time optical disc decryption engine to bypass DRM protections in DVDs and Blu-ray discs. Apparently it was quite popular in digital piracy circles, but it was shut down in 2024 (likely due to legal issues). This has left it impossible for users to obtain or renew licenses, rendering the software unusable unless you previously had a lifetime license. So I figured why not try to crack it? Surely it wouldn't be too hard.

Well, it ended up being a bit more involved than I anticipated.

Note: I feel it's okay to write this post given the software is abandoned and the company behind it no longer exists. With that said, if you are an entity with legal issues with this post, please feel free to email me.

Initial analysis

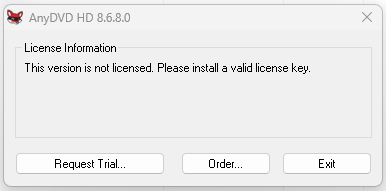

Since the official website is no longer up, I had to find a download on Wayback Machine. I installed it and ran the program and was met with this window:

And of course the buttons to request trial or order a license don't work since their website is down.

So I opened the binary in IDA and took a look at WinMain.

int __stdcall WinMain(HINSTANCE hInstance, ...) {

// ...

if (GetVersionExA(&VersionInformation) && VersionInformation.dwPlatformId == 2)

v7 = (const CHAR *)sub_6F42A0(-467510381, -1184185502, -551434704, -756695388);

else

v7 = (const CHAR *)sub_6F42A0(-1556658173, -1202221158, -1741367911, -740756901);

v18 = (const CHAR *)sub_6F42A0(1141103167, -2061808740, 2130724375, -292276666);

dword_D0F0F4 = RegisterWindowMessageA(v18);

// ...

}We're immediately faced with our first challenge: every string in the binary is encoded. Every single one. All plaintext is run through a function that XORs it at runtime, so searching for strings in the binary yields absolutely nothing useful.

String decoding

The decoding calls in WinMain have four seemingly arbitrary integers as arguments. IDA decompiles the decoding function as:

int __cdecl sub_6F42A0(int a1, int a2, int a3, int a4) {

// ...

EnterCriticalSection(&stru_D15D5C);

v4 = sub_6F40F0(a2, a3, a4, 1);

LeaveCriticalSection(&stru_D15D5C);

return v4;

}This looks like it just drops a1 and forwards the rest to an inner decoding function. But IDA's decompilation is misleading here; the inner function sub_6F40F0 uses a __usercall convention where its first argument is passed in eax, and the wrapper computes that register before the call. Looking at the actual assembly:

mov eax, [ebp+arg_8] ; eax = arg2

push eax ; stack: arg2

xor eax, [ebp+arg_0] ; eax = arg2 ^ arg0

push ecx ; stack: arg1 (ecx was loaded earlier)

xor eax, 3B03BD71h ; eax = arg2 ^ arg0 ^ 0x3B03BD71

add eax, offset 0xABB428 ; eax = 0xABB428 + (arg2 ^ arg0 ^ 0x3B03BD71)

call sub_6F40F0So the wrapper computes a data pointer from arg0, arg2, and a hardcoded constant + base address, passes it in eax, and pushes the remaining arguments onto the stack. The inner function sub_6F40F0 receives:

a1(eax): pointer to encoded data, computed as0xABB428 + (arg2 ^ arg0 ^ 0x3B03BD71)a2(stack):arg1from the call sitea3(stack):arg2from the call sitea4(stack):arg3from the call sitea5(stack):1(character width, hardcoded by wrapper)

The inner function then derives the string length and XOR mask from the remaining arguments:

_WORD *__usercall sub_6F40F0@<eax>(

_WORD *a1@<eax>, int a2, int a3, int a4, int a5)

{

v25[0] = 0x6B8F7DD1;

v25[1] = 0x3B0F7DD1;

v5 = (unsigned __int16)(a2 ^ *a1) ^ 0x7DD1; // XOR arg with 2-byte header at data ptr

v8 = a4 ^ a2 ^ 0x6B8F7DD1; // string length = arg3 ^ arg1 ^ constant

v11 = a5 * v8; // total bytes to decode (a5=1, so just v8)

// Main loop: decode 4 bytes at a time

v13 = 4 * (v11 >> 2);

for (v12 = 0; v12 < v13; v12 += 4) {

v16 = (v12 >> 2) & 1; // alternates 0, 1, 0, 1...

v17 = v25[v16] ^ *(_DWORD *)&encoded[v12]; // XOR with constant

*(int *)(output + v12) = *((int *)&a2 + v16) ^ v17; // XOR with arg

}

// Tail: remaining 1-3 bytes

for (v18 = v13; v18 < v11; v18++) {

v22 = *((_BYTE *)v25 + (v18 & 7)) ^ encoded[v18];

*(output + v18) = *((_BYTE *)&a2 + (v18 & 7)) ^ v22;

}

}The (v12 >> 2) & 1 alternates between 0 and 1 every 4 bytes. When it's 0, the encoded dword is XORed with v25[0] (0x6B8F7DD1) then with a2. When it's 1 it's XORed with v25[1] (0x3B0F7DD1) then with a3. Since x ^ a ^ b == x ^ (a ^ b), this is equivalent to XORing each byte against a repeating 8-byte mask:

mask[0..3] = little-endian bytes of (a2 ^ 0x6B8F7DD1)

mask[4..7] = little-endian bytes of (a3 ^ 0x3B0F7DD1)The 2-byte header at *a1 is consumed by the v5 check but not included in the output. So from a single call site sub_6F42A0(arg0, arg1, arg2, arg3), the wrapper and inner function together derive:

- data address:

0xABB428 + (arg2 ^ arg0 ^ 0x3B03BD71)(computed in wrapper assembly) - string length:

arg3 ^ arg1 ^ 0x6B8F7DD1(computed in inner function) - 8-byte XOR mask:

pack('<II', arg1 ^ 0x6B8F7DD1, arg2 ^ 0x3B0F7DD1)(used in XOR loop)

All four arguments contribute to at least two of these derivations, so there isn't really a separation of functionality between the arguments.

There are multiple decoder variants throughout the binary. Each wrapper computes the data pointer differently; sub_6FAA70 uses base 0xB04310 with constant 0x3BF1F5AA, sub_6FAD50 uses base 0xB04460 with 0xB44E2B42, etc. Each has its own pair of mask constants for the XOR loop. I reverse engineered 7 variants and wrote a Python script that reimplements all of them:

DECODERS = {

0x6FAA70: {'xor_const': 0x3BF1F5AA, 'data_base': 0xB04310,

'v20_0': 0x7154F8C0, 'v20_1': 0x3BF1F5AA},

0x6FAD50: {'xor_const': 0xB44E2B42, 'data_base': 0xB04460,

'v20_0': 0x474F87D2, 'v20_1': 0xB44E2B42},

# ... 7 variants total

}

def decode_string(arg1, arg2, arg3, arg4, decoder, pe):

data_va = decoder['data_base'] + ((arg1 ^ arg3 ^ decoder['xor_const']) & 0xFFFFFFFF)

length = (arg4 ^ arg2 ^ decoder['v20_0']) & 0xFFFFFFFF

mask = struct.pack('<II', (arg2 ^ decoder['v20_0']), (arg3 ^ decoder['v20_1']))

raw = pe.get_data(data_va - image_base, length + 2)

return bytes(b ^ mask[i % 8] for i, b in enumerate(raw[2:2 + length]))License validation

Now that we have a string decoder we can actually read what the binary is doing. I started tracing from WinMain looking for anything license-related. Eventually I landed on a large function at 0x6F6C20. The first thing it does is use SHGetSpecialFolderLocation with CSIDL 35 (CSIDL_COMMON_APPDATA, i.e. C:\ProgramData) to build a path, then appends some decoded strings to it. Running those through my decoder gave me \RedFox\AnyDVD\ and AnyDVD.lic, so the license file should be at C:\ProgramData\RedFox\AnyDVD\AnyDVD.lic.

The function reads the file and compares each line against a decoded string. Decoding the comparison targets reveals a PEM structure; it's looking for -----BEGIN LICENSE----- and -----END LICENSE-----, and collects the base64-encoded content in between.

The base64-decoded bytes get fed into a parsing function at 0x4DE250. This function reads the first byte, masks off the top 3 bits, and switches on them:

// sub_4DE250 - binary format parser

switch (*(_BYTE *)(offset + *this) & 0xE0) {

case 0x00: /* read integer */ break;

case 0x20: /* read negative int */ break;

case 0x40: /* read byte string */ break;

case 0x60: /* read text string */ break;

case 0x80: /* read array */

count = sub_4DDA90(0, 1);

for (i = 0; i < count; ++i)

sub_4DE250(/* recurse */); break;

case 0xA0: /* read key-value map */

count = sub_4DDA90(0, 1);

for (i = 0; i < count; ++i) {

sub_4DE250(/* key */);

sub_4DE250(/* value */);

} break;

case 0xE0: /* special/tag */ break;

}This binary format turns out to be CBOR, which is basically a binary version of JSON. So now we can figure out what data is actually stored here.

Outer CBOR

The parsing function at 0x6F6260 takes the decoded bytes and runs them through the CBOR parser. It checks that the result is either a CBOR array (type 0x80) or map (type 0xA0) with at least 6 elements. Then it starts pulling things out by index.

I couldn't immediately tell what each field meant, but I could see what the code does with them. Element 0 is a small integer that gets stored but never seems particularly important. Element 2 is also a small integer. Elements 4 and 5 are byte strings. Element 5 is always exactly 64 bytes, while element 4 is variable-length.

The function later passes elements 2, 3, 4, and 5 to a virtual method on an AnyDVDLicenseEncryptionHandler object (I got the class name from RTTI data). The vtable dispatch lands at sub_77D280:

// sub_77D280 - outer decrypt dispatcher

char __thiscall sub_77D280(void *this, int a2, int a3,

int a4, _DWORD *a5, int a6, int a7, int a8)

{

switch (a2) { // a2 = element 2 (small integer)

case 0: case 1: case 2: case 3:

case 7: case 10: case 11: /* ... */

// First call: decrypt element 4 using element 5 as key material

result = (*(vtable + 20))(this, a2, a4, a5, a8, a6, a7);

if (result)

// Second call: uses element 3 and the decrypted output

result = (*(vtable + 24))(this, a3, a8, *a5, a6, a7, 0, 0);

break;

default:

result = 0;

}

}So it makes two vtable calls. The first one (vtable+20) uses element 2 to select a decryption mode and element 5 as key material to decrypt element 4. The second call (vtable+24) uses element 3 on the decrypted result, though I wasn't sure what for at this point. Following the first vtable call into DecryptLicenseDispatcher at 0x77D4D0:

// DecryptLicenseDispatcher (vtable+20 handler)

char __thiscall DecryptLicenseDispatcher(void *this, int mode,

void *blob2, size_t *out_size, char *output, void *ciphertext, int ct_len)

{

switch (mode) {

case 0:

memcpy(output, ciphertext, *out_size); // mode 0: no encryption

return 1;

case 1:

case 2:

if (mode != 1 && mode != 2) goto fail;

// Initialize custom SHA-256 state:

v10[38] = -1453830564; // 0xa9584e5c

v10[39] = -1166656343; // 0xba763ca9

v10[40] = 1644259574; // 0x620168f6

v10[41] = 1876643603; // 0x6fdb4f13

v10[42] = -1997984821; // 0x88e92bcb

v10[43] = -1857071185; // 0x914f57af

v10[44] = -991952110; // 0xc4e00312

v10[45] = -1572863949; // 0xa2400033

v10[4] = 128; // initial byte counter

sha256_update(blob2, ct_len); // hash the 64-byte blob

sha256_finalize(); // get 32-byte digest

aes_init_key_dec(v11); // first 16 bytes = AES key

if (mode == 1) {

aes_cbc_decrypt(*out_size, ciphertext, v10/*iv*/, v11/*key*/, output);

*out_size -= output[*out_size - 1]; // strip PKCS7 padding

} else {

aes_cfb_decrypt(v11, v10, ciphertext); // mode 2: CFB

}

return 1;

// modes 10-17: different key derivation ...

}

}Now I could map the outer structure: element 2 is the encryption mode (0=none, 1=AES-CBC, 2=AES-CFB), and element 5 is the 64-byte blob that gets hashed to derive the AES key and IV for decrypting element 4. But I still needed to figure out the hash.

Custom SHA-256

The hash function called on the 64-byte blob has the familiar structure of SHA-256: the same 64 round constants (0x428a2f98, 0x71374491, ...), the same compression logic with Ch, Maj, and sigma functions. But the initial state values loaded above are not the standard SHA-256 IVs:

Standard: 0x6a09e667 0xbb67ae85 0x3c6ef372 0xa54ff53a ...

This code: 0xa9584e5c 0xba763ca9 0x620168f6 0x6fdb4f13 ...And the byte counter starts at 128 instead of 0. This means the SHA-256 padding block encodes a total message length of 128 + 64 = 192 bytes = 1536 bits, even though only 64 bytes were actually fed in. The output is a 32-byte hash split into a 16-byte AES key and a 16-byte IV.

I could also see the AES-CBC decryption loop at 0x6F9D30, which is standard CBC with the IV XOR:

// aes_cbc_decrypt at 0x6F9D30

while (blocks--) {

save_ct = src[0..15]; // save ciphertext block

aes_decrypt_block(aes_ctx, dst); // decrypt in place

dst[0..3] ^= iv[0..3]; // XOR with IV (or previous ciphertext)

iv = save_ct; // previous ciphertext becomes next IV

dst += 16;

}After decryption, it strips PKCS7 padding: *out_size -= output[*out_size - 1]. My Python reimplementation of all this is below:

def derive_key_iv(blob2):

H = [0xa9584e5c, 0xba763ca9, 0x620168f6, 0x6fdb4f13,

0x88e92bcb, 0x914f57af, 0xc4e00312, 0xa2400033]

H = sha256_compress(H, blob2)

padding = bytearray(64)

padding[0] = 0x80

struct.pack_into('>Q', padding, 56, 1536) # (128+64) * 8 bits

H = sha256_compress(H, bytes(padding))

out = b''.join(struct.pack('>I', h) for h in H)

return out[:16], out[16:32] # key, ivInner CBOR

After AES decryption, the result is another CBOR structure, this time a map. The function at 0x6F6C20 pulls values out by integer key and stores them in globals:

// 0x6F6E52 - extract serial (key 4)

v15 = CBORExtractInteger(CBORGetElement(4));

*g_LicenseSerial = v15;

// 0x6F6F2A - extract and check key 3

v19 = CBORGetElement(3);

*g_LicenseIssueDate = CBORExtractInteger(v19);

// 0x6F6F43 - extract key 8

v20 = CBORGetElement(8);

*g_LicenseExpiration = CBORExtractInteger(v20);

// 0x6F6F5C - extract key 5 (string)

v21 = CBORGetElement(5);

customer_name = CBORExtractString(v21);I named the globals by tracing how they're used later. The serial gets displayed in the UI. The expiration timestamp gets compared against the current time:

// CheckLicenseExpiration at 0x6F51F0:

return !expiration || expiration > _time64(0);There's also a peculiar parity check on the issue date:

// CheckIssueDateParity at 0x6E6610:

if (!g_LicenseIssueDate) return 1; // fail

return *g_LicenseIssueDate & 1; // fail if oddFor reasons inexplicable the issue date timestamp must be even. License validation fails if you choose an odd Unix timestamp.

There's also a hardcoded serial number blacklist in the binary at 0xD6C020, a table of 1119 banned serials (starting with 12345678). CheckSerialRevocation at 0x6F52C0 just walks the table comparing each entry, so I had to pick a serial that wasn't in there.

Initial license generator

At this point I had enough to write a license generator. Element 5 (the 64-byte blob) didn't seem to be verified at this stage; the user-mode code just hashed it to derive the AES key. I could set it to 64 zero bytes and as long as I encrypted the inner map with the resulting key, the decryption would succeed.

blob2 = b'\x00' * 64

key, iv = derive_key_iv(blob2)

inner = bytearray()

inner.extend(bytes([0xa5])) # 5-element CBOR map

inner.extend(cbor_uint(2)); inner.extend(cbor_uint(1)) # key 2 = 1

inner.extend(cbor_uint(3)); inner.extend(cbor_uint(1672531200)) # key 3, even

inner.extend(cbor_uint(4)); inner.extend(cbor_uint(99999999)) # key 4, serial

inner.extend(cbor_uint(5)); inner.extend(cbor_str("henry")) # key 5, name

inner.extend(cbor_uint(8)); inner.extend(cbor_uint(0)) # key 8, no expiry

padded = bytes(inner) + bytes([pad_len] * pad_len) # PKCS7 padding

ciphertext = AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CBC, iv).encrypt(padded)

outer = bytearray([0xa6]) # 6-pair CBOR map

# ... keys 0-3 are small integers, key 4 is ciphertext, key 5 is blob2I generated the license, copied it to the right path, and launched the program. It accepted the license and started up. I could see my serial number in the UI. So are we done?

Not quite. After exactly 2 minutes and 50 seconds, the program silently closed.

The inexplicable program exit

My first lead as to why the program exited was a WM_TIMER handler in the Window Procedure at sub_6EF620. Timer ID 7 fires every 30 seconds and sends command 406 to an object at dword_D126D8:

case 7:

KillTimer(hWnd, 7);

EnterCriticalSection((LPCRITICAL_SECTION)(dword_D126D8 + 1012));

if (sub_7E55C0(dword_D126D8, 406, 1))

v34 = sub_432800();

LeaveCriticalSection((LPCRITICAL_SECTION)(dword_D126D8 + 1012));

switch (v34) {

case 0: SetTimer(hWnd, 7, 0x7530, 0); break; // 30 sec, keep going

case 2: case 3: case 4: case 5: case 6: // blacklist & close

PostMessageA(hWnd, WM_CLOSE, 0, 0); break;

case 7: sub_6F5860(1); break; // "shutting down"

}I initially assumed dword_D126D8 was a handle to the kernel driver and that the exit came through status 7. The program ships with a kernel driver (ElbyCDIO.sys) for disc decryption, and commands 405 and 406 being sent through a critical-section-protected object seemed to fit that model. I spent a long time trying to trace the command dispatch through the driver communication layer, going in circles. There just didn't seem to be any further license validation in this path, and I couldn't understand how this timer would hit 2:50 with a 30 second interval.

It was at this point I started trying to pursue dynamic analysis. Unfortunately, I'm a bit of a static analysis one trick. The binary had various anti-debugging mechanisms that prevented breakpoints and binary patching. I'm sure an experienced software cracker would know exactly how to circumvent these protections but unfortunately I couldn't figure it out (though I honestly didn't try for more than a couple hours, I already felt committed to doing this statically).

I hate NTFS

While trying to debug, I ran into a confusing problem: my license generator was working fine, then suddenly the program started showing "license is invalid" on startup. Even reinstalling didn't fix it.

I traced the error message back to sub_6F5300, which checks if a serial number is blacklisted. The interesting part was where it stores the blacklist. After some struggling with the string decoder, I decoded the path components:

\RedFox:AnyDVD

The colon is not a typo. It's an NTFS Alternate Data Stream. The full path is C:\ProgramData\RedFox:AnyDVD, a hidden data stream attached to the RedFox folder, invisible to Explorer and dir. The program uses GetPrivateProfileIntA and related functions to read and write INI-formatted serial blacklist data in this hidden stream.

When certain paths are hit in the program, the program permanently blacklists the serial here. This had apparently happened during one of my debugging attempts, so every subsequent launch rejected my license before it even got to any secondary validation. I was able to find a utility that wiped the stream.

I will never get back the hours you took from me, NTFS.

A breakthrough

Eventually I found the one thing I could do dynamically: get a backtrace. Specifically in WinDbg. I had been trying to use x64dbg and it never gave me a backtrace on program exit. But for some reason when I used WinDbg I got a backtrace. I attached to the process and let it hit the exit, and noticed the exit code was -1, not a clean shutdown through WM_CLOSE. The stack trace at exit landed inside a massive function, thousands of lines of decompilation with a huge switch statement. It seemed to exit in case 184.

I was looking through all the cases and I had a bewildering realization: this was a Java bytecode interpreter. The process was being killed from inside the Java VM, not from the window procedure.

I traced dword_D126D8 back to its creation in sub_6F0A30:

int sub_6F0A30() {

v0 = operator new(0x448u); // allocate 1096 bytes

v2 = sub_48B390((int)v0, v1, 0); // constructor chain

// ... initialization ...

sub_7E55C0(v2, 405, 0, // send command 405 with license data:

*dword_D15C50, *(dword_D15C50+4), // compile timestamp

license_path, // path to AnyDVD.lic

g_LicenseSerial, // serial, issue date, expiration

g_LicenseIssueDate,

g_LicenseExpiration,

&dword_D03AC8, 1867789201, // crypto tables

&byte_D03BE8, 182052321,

&unk_D03AE8, 182052321);

return v2;

}The constructor chain confirmed it: sub_48B390 calls sub_738300, which sets *this = &CBDJJavaMachine::vftable. Following the inheritance (CBDJJavaMachine extends CADVDJavaMachine extends CJavaMachine), this is a full Java bytecode interpreter embedded in the binary. Command 405 sends my license data to the Java VM at startup. Command 406 polls it for a validation result every 30 seconds.

The license validation doesn't happen in the kernel driver. It happens in Java.

BDPHash.bin

So the Java VM runs bytecode from somewhere. I traced the file loading code in the VM initialization and found it reading a file called BDPHash.bin from the program directory, 3.6 MB of what looked like pure entropy. It passes the data through a decryption routine that operates on 64-byte blocks, using indices derived from a 64-byte header at the start of the file to look up keys from a table of 57 AES-128 keys at 0xA54588 in the binary:

idx1 = header[(block_index + 11) % 64] % 57 # key derivation input

idx2 = header[(block_index + 17) % 64] % 57 # IV

idx3 = header[block_index % 64] % 57 # key for derivation

derived_key = AES_ECB_DECRYPT(KEY_TABLE[idx1], KEY_TABLE[idx3])

plaintext = AES_CBC_DECRYPT(ciphertext, derived_key, KEY_TABLE[idx2])After one layer of decryption, the output starts with another 64-byte header followed by more ciphertext. It's double-encrypted with the same algorithm. Decrypting the second layer finally produces a ZIP file signature (PK\x03\x04). Inside were about 30 Java classes in com/sly/ and some resource files in srsrc/.

But several of the important classes had a twist.

Class encryption

I opened the ZIP and started looking at the class files. Most had the standard Java magic CA FE BA BE and decompiled fine. But seven of them, including Sbj.class (the entry point) and Kc.class (the validation logic), had the magic bytes BC 3B instead. Opening them in a Java decompiler just produced errors.

To understand the BC3B format I needed to find the class loading code. This turned out to live in one of the binary's .kitext sections, six encrypted code regions (.kitext1 through .kitext6) that are decrypted at runtime using TEA-64-CFB. It seemed that the decryption key was derived from CRC32 hashes of the binary's code sections. I spent a long time trying to statically reimplement this but I could never get it right. Eventually I realized I could take a process memory dump while the program was running and I was able to get the decrypted sections from that.

With the decrypted .kitext2 available, I found the class loader at 0x84e9f3. It checks cmp cx, 0x3bbc (little-endian for BC3B). If the magic matches, it runs a decryption routine before passing the class to the normal parser. The decryption uses a seeded MWC (Multiply-with-Carry) PRNG acting as a stream cipher (genuinely who the hell wrote this what the fuck):

state1 = (0x7FFF7FFF - magic_xor) & 0xFFFFFFFF

state2 = magic_xor

for each byte:

state1 = ((state1 & 0xFFFF) * 36969 + (state1 >> 16)) & 0xFFFFFFFF

state2 = ((state2 >> 16) + (state2 & 0xFFFF) * 18000) & 0xFFFFFFFF

keystream_byte = state2 & 0xFFThe cipher selectively encrypts only the meaningful content (UTF-8 string data and Code attribute bytecode) while leaving the class file structure (constant pool tags, indices, access flags) in plaintext. The UTF-8 lengths are XORed with the lower 16 bits of magic ^ 0xBEBAFECA. This means you can still parse the class file structure without decrypting, but the actual strings and code are gibberish.

The key insight for decrypting BC3B classes was that the full 4-byte magic is BC 3B xx yy where the last two bytes differ per class file (e.g. BC 3B DA B1 for Sbj.class, BC 3B 71 B4 for Kc.class). XORing these 4 bytes with 0xBEBAFECA produces the magic_xor that seeds the MWC state, so each class gets a different keystream.

How the Java code kills the process

With the classes decompiled, the first thing I wanted to understand was how the Java VM was calling ExitProcess. The answer turned out to be com.sly.Ex, a native function execution bridge. Ex.getInstance("kernel32.dll") parses the PE export table of kernel32 via a virtual filesystem ("://M/1" maps to process memory), and builds a HashMap mapping Java String.hashCode() values of export names to their addresses. Then Ex.ex(long address, Object[] args) is a static native method that calls the resolved function directly.

The class Shed holds a static Ex instance bound to kernel32.dll. So Shed.ex.ex(hashCode, args) can call any kernel32 function by name hash. The actual kill sequence lives in Kc.gbt(), called periodically from Kc.idp():

private void gbt() {

if (gb && (dgbt == 0L || System.currentTimeMillis() > dgbt)) {

Random var1 = new Random();

switch (dgb) {

case 0:

dgb++;

dgbt = System.currentTimeMillis() + 120000L; // 2 min timer

// Phase 0: corrupt process memory at targeted offsets

RandomAccessFile var8 = new RandomAccessFile("://M/1", "rw");

for (int i = 0; i < sml.length; i++) {

if (sml[i] != 0) {

var8.seek(sml[i] - 1);

for (int j = 0; j < sms[i]; j++)

var8.writeByte(var1.nextInt() & 0xFF);

}

}

break;

case 1:

dgb++;

dgbt = System.currentTimeMillis() + 2000L;

go(); // Phase 1: ExitProcess(-1)

break;

case 2:

// Phase 2: 300 random memory writes as fallback

// ...

}

}

}The gb flag is set from idp(), which runs periodically. After 20 seconds, if a0 (validation passed) is still false, gb goes to true and gbt() starts the destruction sequence. But idp() also does additional checks once a0 is true, reading license fields directly from process memory via the "://M/1" virtual filesystem and comparing them against the values in the kkl registry:

void idp() {

this.gbt();

if (te() > 20000L && (dd & 1) == 0) {

dd |= 1;

if (!a0) {

gb = true; // validation didn't pass after 20 seconds

}

} else if (a0 && (dd & 2) == 0) {

dd |= 2;

// Read values directly from process memory

RandomAccessFile var2 = new RandomAccessFile("://M/1", "r");

var2.seek(ade - 1L);

var3 = swap(var2.readLong()); // read expiration from native memory

// ... read serial and issue date similarly ...

if ((Long)kkl.get(2) != 1L) { a11 = 3; gb = true; } // key 2 check

if (var9 != var3) { a11 = 4; gb = true; } // expiration mismatch

if (var5 != var11) { a11 = 6; gb = true; } // serial mismatch

if (var13 != var7) { a11 = 5; gb = true; } // issue date mismatch

}

}So even if the Ed25519 signature verifies, the Java code cross-checks the license fields against what the native binary stored in memory. If anything doesn't match, a11 gets set to a diagnostic value (3-6) and gb triggers the kill sequence.

gbt() then starts a three-phase destruction: first it writes random bytes over specific memory locations (corrupting the process), waits 2 minutes, then calls go() which resolves ExitProcess by hash and calls it with argument -1. The Timer 7/status code mechanism wasn't actually being hit; it was the Java exit through the native function bridge all along.

Further license validation

Now I understood the kill mechanism, but I still needed to figure out what the actual validation checks. The decompiled code was obfuscated (single-letter class names, single-letter method names) but functional. I started from the entry point com.sly.Sbj and traced the call chain.

The validation lives in a class called Kc. Its constructor loads srsrc/ckmap.bin from inside the ZIP, parses it as a CBOR map, and populates a crypto container (Cns) with the keys:

// Kc constructor (vineflower decompilation)

public Kc() {

byte[] var1 = Shed.gres("srsrc/ckmap.bin");

CBOR var2 = new CBOR();

var2.setData(var1);

HashMap var4 = (HashMap)var2.getValue();

Object[] var5 = var4.keySet().toArray();

for (int var6 = 0; var6 < var5.length; var6++) {

int var7 = ((Long)var5[var6]).intValue();

byte[] var8 = (byte[])var4.get(var5[var6]);

if (var7 >= 0)

cns.aks(var7, var8); // positive keys → signature verification keys

else

cns.ake(-var7, var8); // negative keys → encryption keys

}

// ...

}The license then gets parsed in G3RK.set(). This is where the outer CBOR structure I'd reversed from the native code gets processed again on the Java side. It casts the parsed CBOR to an ArrayList, pulls out the encryption type, signature type, ciphertext, and signature by index, then calls Cns.dav():

// G3RK.set() - license parsing and validation

public boolean set(String var1, Cns var2) {

var1 = strip(var1);

byte[] var3 = d64(var1); // base64 decode

CBOR var4 = new CBOR();

var4.setData(var3);

Object[] var5 = ((ArrayList)var4.getValue()).toArray();

int var6 = ((Long)var5[0]).intValue(); // format version

int var7 = ((Long)var5[2]).intValue(); // encryption type

int var8 = ((Long)var5[3]).intValue(); // signature type

if (var6 == 0 && (var7 == 1 || var7 == 2)

&& (var8 >= 1 && var8 <= 6 || var8 == 999)) {

byte[] var9 = (byte[])var5[4]; // ciphertext

byte[] var10 = (byte[])var5[5]; // signature

byte[] var11 = var2.dav(var7, var8, var9, var10); // decrypt + verify

if (var11 != null) {

// ... parse inner CBOR, check key 3 parity vs sig type ...

return true;

}

}

return false;

}Cns.dav() does the decrypt-then-verify:

public byte[] dav(int encType, int sigType, byte[] data, byte[] sig) {

byte[] decrypted = d(encType, data, sig); // decrypt

if (decrypted == null) return null;

if (v(sigType, decrypted, sig)) // verify signature

return decrypted;

return null;

}The d() method does the same custom-SHA-256-to-AES-key derivation I'd already reversed from the native code. The v() method does signature verification. For signature types 1-20, it looks up a 32-byte key from the ks HashMap by type number, then creates an EdDSAEngine and EdDSAPublicKey:

public boolean v(int type, byte[] data, byte[] sig) {

// ...

byte[] keyBytes = (byte[])this.ks.get(new Integer(type));

if (keyBytes == null) return false;

EdDSAEngine engine = new EdDSAEngine();

EdDSAPublicKey key = new EdDSAPublicKey(keyBytes);

try {

engine.initVerify(key);

engine.update(data);

return engine.verify(sig);

} catch (Exception e) { return false; }

}The EdDSA classes were among the unencrypted classes in the ZIP. Reading through them, I confirmed they implement standard Ed25519 (the curve parameters in EdDSANamedCurveTable use the standard field prime, d constant, base point, and SHA-512 as the hash). So the 64-byte blob in the license isn't just a key derivation input like I'd assumed. It turns out it's actually an Ed25519 signature, and the second layer of validation verifies it against a public key from ckmap.bin.

Patching the public key

Now I had a plan. The outer CBOR structure uses signature type 2, which means v() looks up key 2 from the ks HashMap, which comes from ckmap.bin. If I generate my own Ed25519 keypair, replace the 32-byte public key for key 2 in ckmap.bin, re-encrypt BDPHash.bin with both layers, and sign licenses with my private key, the signature should verify.

ckmap.bin is stored uncompressed inside the ZIP, so I could patch the 32 bytes directly, update the CRC32 in the ZIP local and central directory headers, then re-encrypt through both AES layers. I also had to change my license generator to produce a real Ed25519 signature instead of 64 zero bytes, and switch the outer structure from a CBOR map to a CBOR array (the Java-side parser in G3RK.set() casts it to an ArrayList and accesses elements by index, which presumably only works with arrays).

Well, I tried this and unfortunately I got no change in behavior. I still got an exit after 2 minutes and 50 seconds. So now I needed to debug what was failing. But how would I get output from the Java code? I can't attach a debugger to the embedded VM. I can't set breakpoints in the native code because of the anti-tamper protections. I needed some other way to observe the program's internal state.

Bytecode surgery

I noticed something in Kc.class: it has a method called grs() that queries Windows registry keys via HKLM\Software. If I patched the bytecode to call grs() with a path containing a variable's value, the registry access would show up in ProcMon even if the key doesn't exist. Essentially, I could use failed registry queries as a side channel.

For example, to exfiltrate the value of variable a11, I'd inject:

ldc_w "HKLM"

ldc_w "Software\\C\\A11"

getstatic a11

invokestatic String.valueOf(int)

invokevirtual String.concat

ldc_w "MachineGuid"

invokestatic grs

popThen in ProcMon, I'd see a registry access to HKLM\Software\C\A113, the 3 at the end being the value of a11.

There's a critical constraint though: the patched class must compress to exactly the same size as the original within the ZIP. The BDPHash.bin file size is fixed (for AES block alignment), and changing compressed sizes corrupts the ZIP structure. This meant every bytecode patch required trial-and-error with different padding bytes and compression levels 1-9 until I found a combination that produced an exact match.

To make room for the injected bytecode, I gutted two unused methods (spPrerep and spAutoCheck) and removed some test cases from a lookupswitch table.

Diagnosing the verification failure

With the exfiltration mechanism in place, I patched the public key into ckmap.bin, re-encrypted BDPHash.bin, generated a signed license, and tested. ProcMon showed a11=2, meaning G3RK.set() returned false. The license was rejected somewhere inside the Java validation.

I started binary-searching through the validation code with more bytecode patches. I patched Cns.v() to always return true for signature types 1-20 (a one-byte change: iconst_0 to iconst_1 at the right offset). Now a11=1, so the AES decryption was working but the Ed25519 signature verification was failing.

But why? I had the right public key, the right signature. I further narrowed it down with two more diagnostic patches: one making the "key is null" branch return true, another making the exception handler return true. Tested again, still a11=2. This meant the key was loaded, no exception was thrown, and EdDSAEngine.verify() was legitimately returning false.

I verified my signature was correct using standard Ed25519 outside the program. It verified fine. I'd already confirmed from the decompiled EdDSANamedCurveTable class that they use standard curve parameters, no custom math to worry about. So the key was being loaded, no exception was thrown, the Ed25519 math was running, but it was returning false.

I stared at the Cns.v() code for a while:

public boolean v(int type, byte[] data, byte[] sig) {

// ...

EdDSAEngine engine = new EdDSAEngine();

EdDSAPublicKey key = new EdDSAPublicKey(keyBytes);

engine.initVerify(key);

engine.update(data); // data = decrypted inner content

return engine.verify(sig);

}And then I looked at dav() which calls it:

byte[] decrypted = d(encType, data, sig); // decrypt

if (v(sigType, decrypted, sig)) ... // verify decrypted dataAnd then I looked at AesCrypt.decrypt_cbc():

public byte[] decrypt_cbc(byte[] iv, byte[] ciphertext) {

// ... standard CBC decryption ...

byte padding = result[result.length - 1];

return copyOfRange(result, 0, result.length - padding); // strip PKCS7 padding

}There it is. decrypt_cbc strips the PKCS7 padding before returning. So v() receives the unpadded data. But my license generator was signing the padded data (since you have to pad before encrypting). The signed content didn't match the verified content.

The fix was one line: sign the inner content before adding PKCS7 padding, not after.

# Before (wrong):

padded_inner = inner + padding

signature = private_key.sign(padded_inner)

# After (correct):

signature = private_key.sign(inner)

padded_inner = inner + padding

ciphertext = encrypt(padded_inner)Conclusion

With the padding fix, the license passes all validation. The final keygen is about 200 lines of Python. It generates a fresh Ed25519 keypair, patches the public key into BDPHash.bin, and creates a signed license. It takes about 10 seconds to run (the double-layer AES encryption of the 3.6 MB file is not fast in pure Python) and produces a working crack from a single script.

I don't know what maniac wrote this but they sure did protect their software. I never want to see encryption again.